In a recent MBH4H post, I ruminated on how making mistakes and doing things by accident are intrinsic parts of the creative process. Many of the examples I gave were from my own photographic career, during which I seemed to make stupid mistakes on a fairly regular basis. It was only years later I realized the value of those mistakes, but it certainly wasn't much fun at the time.

I still dream about my days shooting with film. These aren’t pleasant, nostalgia-fueled romanticized dreams of the heady days of analog photography, mind you; these are sweat-inducing, wake-and-bolt-upright night terrors where I lose my bag of exposed film, or it all comes out blank, or something in the camera breaks, and the photos are destroyed, and I am frantically scrambling trying to explain some horrendous fuckup to a client. It’s safe to say I certainly don’t miss photographic film in any way, shape, or form.

Which is why I’ve been genuinely puzzled by the growing trend of shooting on 35mm photographic film. As someone who couldn’t wait to switch to shooting digitally the moment it became viable in the early 2000s, I sincerely hoped I’d never have to use a roll of film again as long as I lived. I assumed most photographers would feel the same, and yet, as of today, there are almost 99 million posts related to film photography on TikTok, 43 million on Instagram, and a Subreddit dedicated to film with over 192K members. Shooting film is “so hot right now.”

And camera manufacturers are taking notice. Last year, Leica sold 5,000 M6 film cameras, ten times as many as they had in 2015—a number so low at the time that the company had apparently considered shutting down production of the M6 entirely. This year is the 70th anniversary of the Leica M series, and instead, there are rumors that a new Leica film camera is in the works. Other manufacturers are also taking notice of the resurgence of film: Pentax recently introduced the PENTAX 17, which uses 35mm.

But considering the billions of photographs that are taken using smartphones and digital cameras, even if millions of photos are shot on film, it’s still niche—at least for now. And that’s OK. Photography is experiencing what the music industry started, a trend I call “Vinylifcation,” i.e., the adoption of an old analog technology for purely aesthetic reasons.

Sales of vinyl are outselling CDs for the second year running, more than 43 million strong, thanks largely to the power of Taylor Swift (yes, I am a huge fan), who had five of the top-selling vinyl albums in 2023, including the top three; 1989 (Taylors Version) was #1 with over a million sales. But kudos, too, to Fleetwood Mac, Rumors sold 200,000 copies. Not bad for an album first released in 1977.

Listening to a vinyl album has an element of ritual with several mechanical steps: Pulling the album from the sleeve, cleaning the grooves, placing it upon the turntable, adjusting the speed, positioning the stylus, etc. In a time when most of us can instantly hear any song or piece of music ever created just by asking our phone or smart speaker to “play something,” playing a vinyl album is a considered, deliberate act, a decision that requires an element of work and our almost complete attention. Vinyl is undeniably cool—it’s no wonder Jony Ive designed a limited edition Linn Sondek LP12 turntable

The same can be said of taking pictures using a film camera, an act that shares the same element of ritual as listening to a vinyl album.

Everything I used to hate about shooting film—not being able to immediately see the photo you’d just taken, the risks of over or underexposing your best shot, the foibles of manual focusing, and the effort of having to find somewhere to process it (unless you process it yourself, in which case, I salute you)—I now understand are the very things that make shooting film so attractive in these terminally online days. The aggravation is the point, especially for the generations that only grew up with digital: Shooting on film is an entirely different way of taking pictures, one that is completely antithetical to using a digital camera or smartphone.

Everything I used to hate about shooting film, I now understand are the very things that make shooting film so attractive in these terminally online days.

Listening to albums on vinyl and shooting photos on film was a trend long before Dall-E and Midjourney appeared, but I suspect that GenAI will further fuel interest in using analog creative tools in general—and not just the work we create but also for the content we consume.

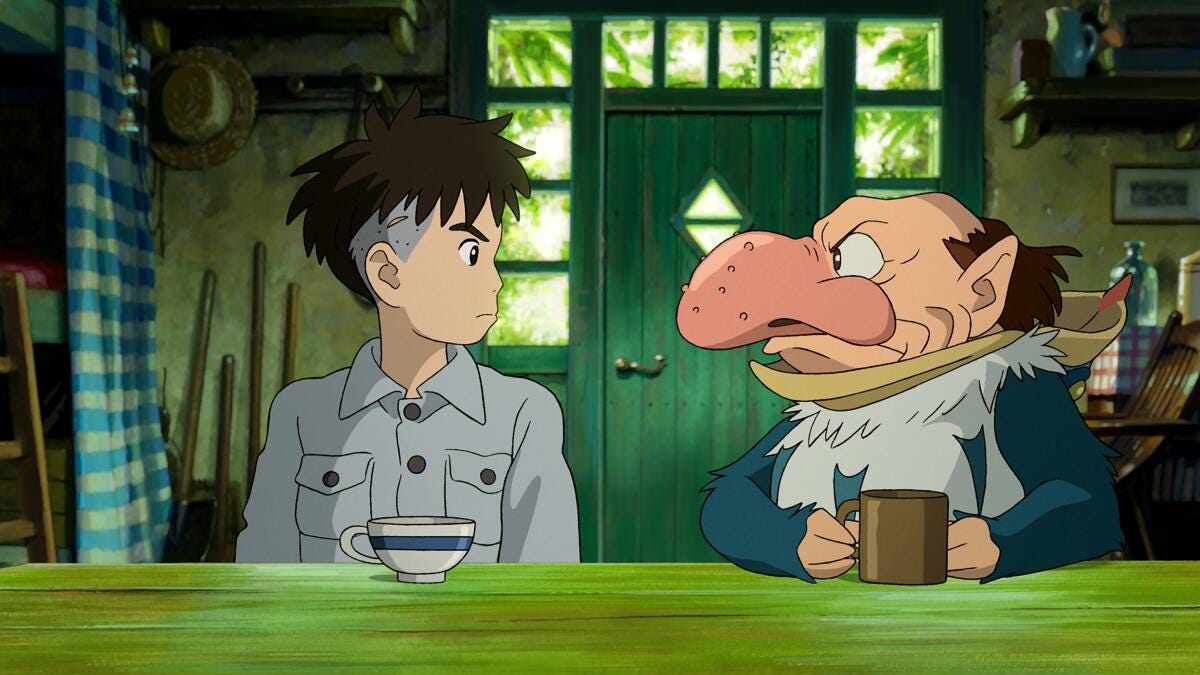

There is something awe-inspiring in those who embrace more analog tools, which we, as a collective culture, like to acknowledge and reward. Earlier this year, Studio Ghibli’s hand-drawn animated film The Boy and the Heron, directed by Hayao Miyazaki, won the Oscar for best animated feature—only the second time a hand-drawn film had won this category since it was introduced in 2002. Miyazaki won the Oscar in 2003 for Spirited Away.

The hand-drawn aesthetic of Miyazaki’s movies is what makes them so special and timeless. I remember randomly stumbling upon Castle in the Sky on TV one afternoon in the late 1980s and marveling at the exquisite watercolor skies and Henry Moore-esque robots. In terms of the creative process involved, there is little difference between Castle in the Sky and The Boy and the Heron despite being made 37 years apart.

Of course, Studio Ghibli isn’t purely analog. The studio has embraced some digital technology, but only sparingly. In an interview in late 2023, cinematographer Atsushi Okui, who has worked with Miyazaki on many of Studio Ghibli’s movies since the early 1990s, explained how the studio approached using digital techniques:

Miyazaki’s first film to use computers was Princess Mononoke. There, the parts where we used digital effects were only about 10 percent of the entire film. We would only use digital effects for special shots, and we used them to bring out the texture in the background, which would be hard to do with only camerawork.

With The Boy and the Heron, we, of course, start out with the animators and background artists, who still use paint or pencil on paper. After that is where we employ digital technology. But we don’t use any kind of 3D rendering when creating the characters themselves. That’s what we don’t do at Ghibli.

As I have written before, I see AI in particular, and lately digital technology in general, as a support system for the creative process, a tool, not a robot. I write notes in my notebook with a pen, not just because it feels better to do so, but because I remember them better, too. I also sketch out ideas using pencil and paper because I want to come to the computer with a well-formed idea that I then have to figure out how to make. I have literally had to search YouTube to learn a technique in Illustrator or Photoshop to figure out how to make something I drew on a notepad with a pen.

To be clear, I am no Luddite; I love technology and still see computers as the future. If I can’t call myself a techno-optimist because Marc Andreessen has co-opted that phrase to mean libertarian shithead, I can at least describe myself as tech-positive, though admittedly slightly less now than I was a few years ago, writing about AI these past few months has diluted my early adopter enthusiasm somewhat.

In a documentary about Miyazaki from 2016, developers of a new AI animation model present it to both Miyazaki and the Studio Ghibli team. It does not go well, and the reactions on their faces are difficult to watch. “I feel like we're nearing to the end of times,” he says in the video. “We humans are losing faith in ourselves.” I think he may have a point.

Shooting on film is an entirely different experience. Yes, digital is easier, but it has also robbed us of much of the experience of taking pictures.