How Nintendo harnessed the power of my brain to upscale The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom

8K is nothing compared to the human mind.

The PlayStation 5 Pro launched earlier this month. Reading Sean Hollister’s very technical and detailed review on The Verge, this latest version of the PlayStation sounds like a beast:

PS5 Pro comes with an extra 2GB DDR5 memory, more than double the storage at 2TB, and—most importantly—a 62 percent faster GPU, with 16.7 teraflops of raw graphical compute. Add an AI upscaling technique called PlayStation Spectral Super Resolution (PSSR), and it’s easily the most potent home console yet made.

Even with Sean’s caveats—not all games will be optimized equally (some not at all), and you need to sit pretty damn close (less than 10 feet) to a very good OLED screen to see the difference in resolution—the PS5 Pro sounds incredibly good. And so it should; it costs $699.99.

Now, compare this raw power with the humble Nintendo Switch. The Switch is well over seven years old, and we’re still awaiting the long-rumored Nintendo Switch 2 (or whatever it’s eventually called), currently slated to launch sometime in 2025. Yet, despite its age, the Switch is now the third most popular gaming console of all time. It is also the first console I’ve ever owned.

Like many, I bought my Switch to play The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild in 2018 and became a novice gamer for the first time. I suspect many others have a similar story, be it Breath of the Wild, Mario Kart or perhaps Animal Crossing, the de facto mascot for many during the early days of the pandemic.

A few years after buying my Switch, I also bought myself a PlayStation 5. The PS5 is a massive difference in raw gaming power. I find myself constantly taken aback by the resolution and sheer fidelity of the games I am playing in 4K at 60 frames per second on a 65-inch OLED TV screen, especially when compared to the lowly 720p of the Switch (1080p when docked). That’s hardly surprising: A PS5, let alone the new PS5 Pro, is umpteen times more powerful than the Switch—which was arguably underpowered even at launch.

Impressed as I am with the glorious 4K fidelity of a game like Death Stranding—where every rock, blade of grass, thread of clothing, surface texture of equipment, down to the individual hairs on Sam Porter Bridges head, are detailed beyond belief—the games I still find the most visually atmospheric are The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild and the even better sequel, Tears of the Kingdom, in all their 720p, 30fps glory.

Where the PS5 Pro relies on a humongous GPU and AI upscaling to render every minute detail in Horizon Forbidden West or F1 24, both BotW and TotK already have access to something way more powerful to do the upscaling on the humble little Nintendo Switch: My brain.

The visual design of BotW and TotK means the games don’t need 4K fidelity to look and feel incredibly real. The designers have gone to great lengths to help these games metaphorically punch well above their weight of pixels and far beyond the capabilities of the Switch’s tired processor.

The landscapes and vistas of Hyrule may not look hyper-realistic on my OLED Switch screen, but they certainly do in my head. This is because director Hidemaro Fujibayashi, producer Eiji Aonuma, and their team have used every visual and artistic trick in the book to fool my brain into upscaling the open world they’ve built to super high resolution.

What consistently strikes me when playing both BotW and TotK is the very clever use of ambient perspective (sometimes described as atmospheric perspective), which gives Hyrule’s landscapes a richness and beauty that feels comparable to Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings iconic trilogy, even at the paltry 720p resolution of the Switch.

Zelda's developers have used every visual and artistic trick in the book to fool my brain into upscaling the open world they’ve built to super high resolution.

Ambient perspective tricks our brains into thinking a two-dimensional scene has three-dimensional depth through a clever combination of tone, color, and contrast. Objects in the distance (mountains, structures) are created with paler and cooler colors and a closer contrast ratio between the sky and land (or sea) than objects in the foreground, which have richer, warmer colors, a wider contrast ratio, and increased sharpness, all of which all combine to create the illusion of depth.

The Sky Islands in Tears of the Kingdom are a perfect example. As Link stands on the edge of The Great Sky Island and looks off towards the horizon, the other floating islands are barely visible in the far distance, pale in tone and color and barely discernible against the sky, while in the foreground, the ripples of the water in the pool and leaves on the trees are punchy, detailed and crisp.

The overall scene may not look real, yet it certainly looks right, which, in turn, makes it look convincingly realistic in my head.

Beyond ambient perspective, both Zelda games also use extremely precise colors in the skies and landscapes, which vary in terms of hue and saturation to convey different times of the day and night. Sunset on the Sky Islands in particular is something to behold (see the main image above). As evening progresses, the colors of the sky grow warmer, richer and tonally closer as the sun sets and the sky is infused with green and pale orange before fading to ceruleans and deep blues of night. The effect looks stunningly accurate.

I suspect green is not one of the colors that first come to mind when thinking of a sunset. But its rarity doesn’t make it feel fake as much as it does special. I saw identical green and orange hues when I once watched the sunrise from the summit of the Haleakalā National Park in Maui, Hawaii. That morning was well over 30 years ago, yet watching the sunset from the Sky Islands in Tears of the Kingdom for the first time took me right back there.

However, ambient perspective alone is not enough to create a convincing landscape. Game designers also need accurate texture and detail in all of the natural elements, and not just the look and feel; these elements have to move and interact convincingly with sunlight, which varies at different times of the day.

Of all the elements most often called out when discussing impressive pixel resolution and fidelity in video games, I’d wager hair (human, animal, or monster) is most often cited—just search Aloy’s hair in the Horizon subreddit, and you’ll see exactly what I mean.

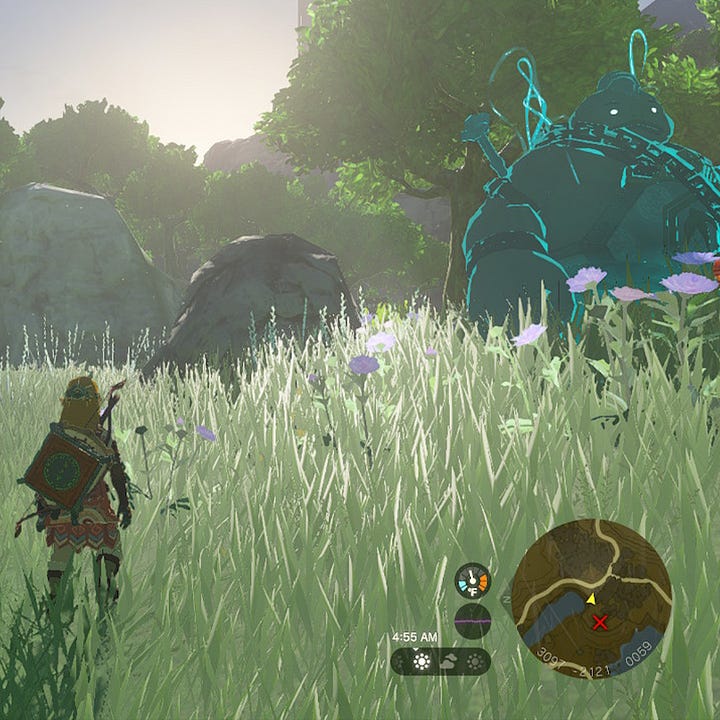

I’m not for one second going to claim that Link’s hair (or any other character’s hair, for that matter) in BotW or TotK is remotely realistic. I will claim that for the grass. When it comes to the grassy plains and hillsides of Hyrule, the game’s designers have managed to render realistic-looking grass by employing some creative distraction techniques: They use very accurate lighting, shade, and natural movement to hide the lack of resolution.

If you look for it you can see the simplicity of the shapes of the individual blades of grass. Yet, when you’re deep into playing the game, focusing on Link, fighting monsters, or riding your horse at speed, the grass, wafting gently in the breeze, occasionally backlit by the sun (complete with occasional J.J. Abrams’esque lens flair) or dappled in the shade of trees, looks So. Damn. Real.

Of course, these same exact techniques of lighting, shade, and natural movement are used in the much higher-resolution landscapes in games played on the PS5. However, in some of these games, the increased resolution can be counterproductive to suspending the players’ disbelief—at least mine. When landscapes and environments are so finely rendered in such sharp detail, I often find it distracting; I don’t know where to look or where to focus.

A perfect example of this is Horizon Forbidden West. The sheer fidelity of this game is genuinely astonishing—and not just Aloy’s aforementioned hair. Every leaf on every tree, every blade of grass, every overgrown building, and every mechanical animal is as crisp as a crispy thing that’s really crisp. It’s undeniably impressive.

And impressive may be the problem. When it comes to natural landscapes (as opposed to man-made structures like cities, spaceships, etc.), fidelity doesn’t necessarily create reality, regardless of whether the landscapes are post-apocalyptic or not. The reason? When everything is sharp or uniformly highly detailed, our brain will tell us that what we’re looking at is fake simply because we don’t see the real world that way.

The human eye sees in extremely high resolution. But that resolution isn’t evenly distributed; it’s concentrated in the center of the eye. As a consequence, our peripheral vision is much lower in resolution. In other words, fuzzy at the edges.

This is why games like Horizon Forbidden West, Jedi Survivor and Star Wars Outlaws all have the same issue for me: There’s too much detail in everything. Playing these games is like watching a movie on a TV with motion smoothing turned on by accident; less Dune: Part Two, more Days of Our Lives.

As a result, my brain is doing the diametric opposite of what it does when I play BotW or TotK: It’s trying to downscale the game to help me make sense of what I am looking at. I find it exhausting—and I’m also convinced this is why I also suffer motion sickness playing these particular games.

As consoles develop over the coming years, I am sure that there will continue to be an arms race for greater and greater resolution and more and more frames per second, particularly for AAA games.

Personally, I’m not convinced that more is necessarily better. As Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom prove so convincingly, sometimes being forced to find creative solutions and workarounds—precisely because a team doesn’t have the luxury of being able to rely on mammoth hardware specs—can be a good thing. It can inspire the use of more artistic and creative techniques, some of which have been around since the Renaissance. As a result, we may see more convincing, beautiful, and inspiring worlds than those that rely on compute power and resolution alone.

I’m inspired to believe that when it comes to video game design, sometimes an artistic solution is better than a technical one. After all, why spend so much time and effort pushing pixels when you can trick the human brain into doing it for you.

Interesting that you jumped in to gaming with BotW on the Switch, because that game originally came out on the Wii U. After that console flopped, it was eventually ported to the Switch, where it obviously saw a lot more people enjoy it.

The first Zelda game developed for the Switch generation was TotK. 💁🏼