It took me over thirty years to appreciate the creative genius of Hayao Miyazaki

I was both early and late to Studio Ghibli.

To date, my relationship with the work of Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli spans 36 years.

During that time, Miyazaki’s creative style has seemingly changed little. That’s the diametric opposite of mine: My creative career has swung wildly in all sorts of directions over the past three decades, some intentional, some not. Likewise, Miyazaki’s work has impacted me in different ways at different times, and I only recently realized just how inspirational and influential it has become.

The first time I saw one of his films, I had no idea who’d made it. I watched it entirely by accident. It was New Year’s Eve 1988, and I was living in Bristol, England, idly flicking through the available TV channels to see what was on when I came across an intriguing animated movie playing on ITV, what I would later know to be Castle in the Sky.

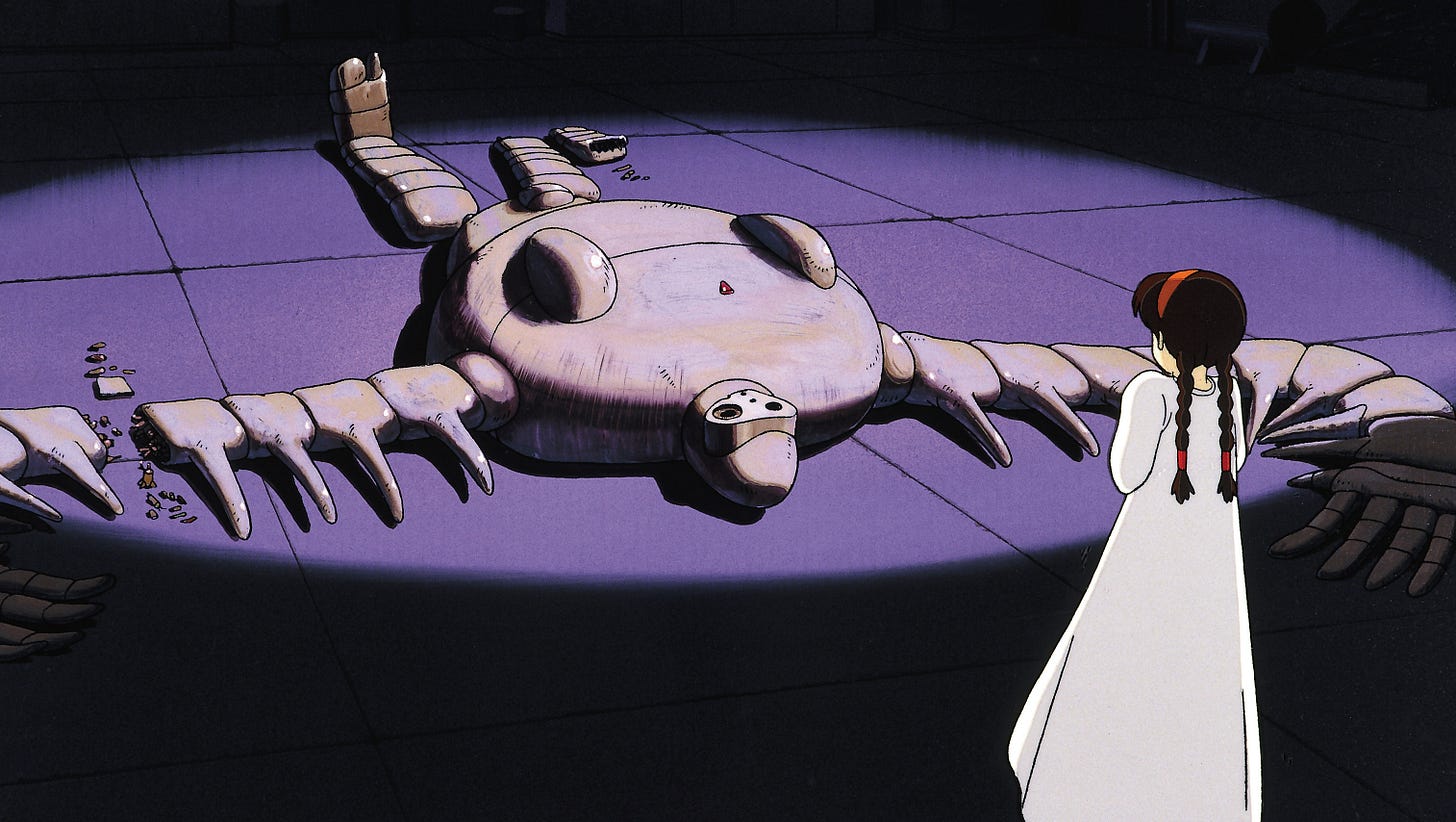

The film had already started: A young girl with black hair and a red headband is being led through a moodily lit cliff-top fortress by a man. They come to a dark room, and he asks her to step inside. Lying on the stone floor of the room is a massive, broken robot. The right foot and part of the left arm were lying separate, exposing gold wires and protruding from the stumps.

The design of the robot was like nothing I had ever seen before. It looked more like a drawing of a sculpture by Henry Moore than C-3PO or RoboCop. I loved it. I was utterly intrigued by the design and the care with which the animator(s) had drawn it; the lighting, shading, and detailing were exquisite. Within a few minutes, the girl with the red headband had accidentally brought the “dead” robot back to life, and it immediately embarked on a beautifully animated destructive rampage on a scale that the Terminator could only dream of. It was positively epic.

I had no idea why any of this was happening. The plot was opaque, but I didn’t care. I was hooked on the visuals: The aforementioned robot; the giant steampunk-esque air battleships; the marauding band of sky pirates led by a bulky, commanding older woman with red pigtails (and very few teeth), and their little flying machines that looked like a cross between the front of an old fighter plane and mini Dune-style Ornithopter; the mysterious floating abandoned city protected by an epic, endless thunderstorm, and home to more of the Henry Moore-esque robots (a few of whom seem happy to tend to the animals and birds); and a secret, dormant weapon capably of laying waste to entire continents. But most of all, I was captivated by the sheer artistry of the film. It was like nothing I’d seen before.

Well, not quite. Some elements of the character design and sound effects seemed vaguely familiar; they reminded me of Marine Boy, an animated series I watched as a young child (and one of the first anime to be shown in the UK). I loved the dolphin and was obsessed with the idea of “Oxygum,” chewing gum that allowed you to breathe underwater—I wanted some of that so badly.

It should go without saying that Castle in Sky was magnitudes better than the clunky, cheaply-made Marine Boy (no offense meant, of course). Castle in Sky had exquisite artistic attention to detail. The backgrounds all had a hand-painted quality, with subtle atmospheric lighting, shading, and subtle movement in the trees, grass, and clouds. I particularly loved the skies: bright blue with fluffy white watercolor clouds, or dark and brooding, pierced by sunlight over an ocean or cut by lightning within the broiling menace of a thunderstorm. The film seemed less like an animated movie and more like a living illustration.

Despite how much I enjoyed the film, I had no idea what it was called at the time. And the film vanished without a trace. As far as I am aware, Castle in Sky disappeared from British screens until 2006. Before then, British Anime fans relied on watching the VHS tapes of the film recorded by their parents on that fateful New Year’s Eve, 1988. As for me, it remained the nameless Japanese animated movie with the fluffy watercolor clouds and Henry Moore robots I once watched by accident.

In the spring of 2020, I was working on artwork to accompany Polygon’s Studio Ghibli Week. As I started pulling source images together for an illustrated montage, I recognized images from that animated film I’d watched 32 years ago. I finally learned its title, and I also learned of the legendary director behind it: Hayao Miyazaki. Castle in the Sky was, it turns out, Studio Ghibli’s first film.

By then, I was already aware of Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli. I remembered him winning the Oscar for Best Animated Feature for Spirited Away in 2003 (the only Japanese movie to have won that award until he did it again in 2023 for The Boy and the Heron), yet I had never seen that film. Sifting through assets for my Ghibli artwork, I also recognized the big gray, fluffy, bunny-like creature with the big smile standing next to the little girl with the red umbrella at a bus stop. But I’d never heard the film's title, My Neighbor Totoro, nor was I familiar with several other icons that made the collage: Kiki’s Delivery Service, Porco Rosso, Princess Mononoke, Howl’s Moving Castle, Ponyo, or The Wind Rises.

Working at Polygon, I found myself surrounded by Studio Ghibli aficionados who could write brilliant essays about the profound loneliness of Kiki’s Delivery Service or when a “...a master makes a meh-ster piece” (still such a great headline) or umpteen other smart deep takes. Yet I was deeply ignorant of almost everything they were writing about other than Castle in the Sky, and even that was a fractured memory.

Now, at this point, I’m sure you’re expecting me to write about how I immediately sat down and started watching all of Studio Ghibli’s back catalog of Hayao Miyazaki masterpieces, especially as, at that time, they had all recently become available to stream for the first time. But you’d be wrong; I only watched the one.

I finally experienced Castle in the Sky from beginning to end. I saw many things I missed in 1988, including the gorgeous opening credits. However, I hated the dubbed English soundtrack. It grated on me. Pazu was a 13-year-old boy who sounded more like a college student, and many of the other characters seemed mildly hysterical most of the time—I’ve since learned that the film had a different English-speaking cast when I watched it in 1988. Despite the voice acting, I still adored the film’s visual style, especially the opening credits; they appealed to the former artist in me.

When I first watched Castle in the Sky in 1988, I was beginning to move away from working as a commercial artist and towards photography. But during my time as an artist, I often painted with watercolors, and I think this is why I was so taken with the movie at the time. I was in awe of the Ghibli animators' use of watercolors and what looked to me like gouache (both tricky mediums at the best of times).

However, by 2020, I hadn’t picked up a paintbrush in decades and had, instead, fully embraced the digital medium. I loved the modern animated works of Pixar and the CGI-rich universes of the Avengers and Star Wars. Though I retained a modicum of nostalgic admiration for Castle in the Sky and still loved its artistry, I couldn’t quite feel the same enthusiasm for Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli that my Polygon colleagues exhibited.

Yet something would happen that would completely upend my appreciation of Hayao Miyazaki and transform me into an ardent fan: I lost my job.

On January 23, 2023, I was let go from Vox Media. Within a week, I decided to return to working for myself. Almost immediately, I landed a project to rebrand Heritage Steel, a storied family cookware company from Tennessee. After seven years of working in digital media, where words and artwork are infinitely adjustable, days and even weeks after publication. Now, I was creating logos and designs that would be stamped or etched into steel pans with a shelf-life of decades. It was an entirely new way of working for me, with no room for mistakes.

The Heritage Steel project also rekindled my desire to sketch with a pencil and draw ideas by hand instead of just picking up a Wacom pen and using a computer. That digital way was too easy, too predictable, too safe. I wanted to come up with the best ideas, not just the first thing that popped into my head. I felt compelled to force myself to draw first and only then work on the final designs on the computer, which often resulted in the need for me to learn new techniques in the process —I watched a lot of YouTube videos that year. Drawing also reignited an interest in Miyazaki’s concept art, which I’d come across while working on Studio Ghibli Week at Polygon.

By the end of 2023, I had bought Castle in the Sky, My Neighbor Totoro, Spirited Away, and Kiki’s Delivery Service and watched them in the original Japanese with English subtitles; no more grating dubbing. In addition to the films, I also bought two hardback books: The first featured concept art from Castle in the Sky; the second was published to coincide with an exhibition of Hayao Miyaki’s work at the Academy Museum in Los Angeles, which ran from fall 2021 to summer 2022.

Reading the Academy book about Miyazaki’s creative process, such as seeing the original imageboards he’d created for My Neighbor Totoro, the bathhouse in Spirited Away, and learning that Lady Eboshi’s mansion in Princess Mononoke was inspired by “Herring Mansion” in Otaru, Hokkaido was nothing short of an inspiration. It not only enhanced my appreciation of Miyazaki’s work but also began to inspire my own work, especially against the backdrop of a burgeoning era of Artificial Intelligence.

It’s clear that Miyazaki works largely by hand and seemingly refuses to use modern technology. Toshio Suzuki, Miyazaki’s longtime producer, said in 2021, “Miya-san doesn’t use a smartphone or personal computer. He doesn’t believe in information that can be easily obtained. He believes in people.”

I also think it’s safe to say that Miyazaki also hates AI. There is a well-known video of a development team from Dwango.Co.Ltd presenting an experimental AI-generated zombie crawling across a floor using its head as an extra limb to the Studio Ghibli team. In the video, Miyazaki looks appalled. He quietly says to the team of dumbfounded developers, “I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.” After the meeting, he added, “I feel the world’s end is near. Humans have lost confidence.”

Yet it’s important to see Miyazaki’s objection to this demonstration of AI in a wider context; it’s more than some Luddite rejection of new technology. He tells the developers that they have no understanding of what pain is or what it means to suffer. He gives the example of a friend who is disabled and has difficulty moving—who may be a man he knew who suffered from Hansen’s disease. Miyazaki often questions what it means to be human and is concerned that “People must live their lives fully.”

Against this backdrop of my own obsession with what exactly defines human creativity, I watched more of Miyazaki’s films over the past few months to try and decode what defines his creativity. I watched Princess Mononoke (which I found surprisingly violent and adult-themed, especially when compared to movies like Totoro), Howl’s Moving Castle, and Ponyo, and I re-watched The Boy and the Heron, Spirited Away, and My Neighbor Totoro. Despite the decades separating these films, the impact of the storytelling and artistry are remarkably consistent—with the possible exception of Ponyo, which is a little kid cartoony at times.

As much as these films helped me discern some of the themes and motifs that reoccur in a Miyazaki movie—at least one scene set on a rich green hillside with a backdrop of a bright blue summer sky with white fluffy clouds or a richly detailed cooking scene—what I found most insightful wasn’t an animated movie, it is a remarkable four-part documentary series from NHK which shadows Miyazaki at work in his studio and at Studio Ghibli over a 10 year period. It’s remarkably intimate and sheds a remarkable insight on Miyazaki’s creative process and how often he struggles with it.

Some of the many standout moments for me are when Miyazaki decides to use pastel chalk for the first time and then proceeds to create an imageboard that defines the entire look of the movie Ponyo; the second is him drawing an emotional scene at a railway station in a storyboard for The Wind Rises using only a few lines in pencil, and then seeing the finished shot in the film.

Yet perhaps the most impressive moment in the entire documentary comes during a screening of The Wind Rises and a sequence depicting the aftermath of the Great Kantō earthquake and fire of 1923: One single four-second shot of the protagonist and a young woman making their way through a crowded street took the Studio Ghibli animators over a year and three months to complete. And by hand. It seems such an extraordinary amount of effort for so little reward. Yet, in many ways, this one shot defines exactly why Miyazaki and his team are so remarkable; the effort is the point.

The Wind Rises, a fictionalized dramatization of the life of Japanese aeronautical engineer Jirō Horikoshi, inventor of the Zero fighter, was widely regarded as Miyazaki’s final film; he announced his retirement two months after its release in Japan on July 20, 2013.Though the subject is decidedly different from Miyazaki’s films’ more common fantasy themes, I found The Wind Rises surprisingly compelling. It’s a beautifully crafted piece of work. But one line in the film really stood out: During a dream sequence towards the movie’s end, the character Giovanni Battista Caproni, the Italian aircraft engineer, says to the protagonist, Jirō Horikoshi, “Artists are only creative for ten years. We engineers are no different. Live your ten years to the full.”

It’s such a peculiar line written by a man who began his career as an animator in 1963 and released his last film, the Oscar-winning The Boy and the Heron, aged 82, and ten years after he’d supposedly retired.

Looking back 36 years to the first time I watched Castle in Sky, I find it remarkable how well the film holds up. Sure, it’s a little rough around the edges, and yes, the sophistication of the art and quality of the animation in Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle, The Wind Rises, and The Boy and the Heron are leagues ahead. Still, at their heart, and despite the decades separating them, all of these films share the same core DNA: the director’s extraordinary imagination and artistic skill.

Hayao Miyazaki turned 84 earlier this month. The Boy and the Heron—which in Japan is titled「君たちはどう生きるか」(Kimi-tachi wa Dou Ikiru ka), which translates to “How will you live?”—may well prove to be his last film. If it is, it is a wonderful finale of an astonishing career. But then again, I have no idea whether Miyazaki is currently in his studio drawing and painting storyboards for something new. I truly hope so.