We’ve been asking, 'What is a photo?' since the invention of photography

AI will make surrealists of us all.

Earlier this month, Google unveiled its new Pixel 9 and Pixel 9 Pro phones—and with them, a bevy of new AI-related features. One of those is “Add Me,” which does “exactly what it says on the tin”: it is a clever way to add a photo of yourself, or someone else, to a group photo by means of Google’s AI seamlessly combining two images together to create a very real looking “fake” group photo.

The relative ease with which the Add Me app does the heavy lifting to create an image—which can be most accurately described as an amalgamation of different frames—led to various commentators across the internet to ask, once again, the perennial question: What is a photo?

Nilay Patel and The Verge have been on this beat for years now. I can remember having some version of this conversation back when I was on the team—and I think that was just in the context of HDR. But with the advent of Google’s “Magic Eraser” tool last year and the new Pixel Studio AI app last week—as well as Samsung’s Galaxy Z Fold 6’s “sketch to image” tool back in July—it’s abundantly clear that the introduction of AI into the mix has supercharged the whole discussion about what, exactly, constitutes a photo in this, the year of our Lord 2024.

The irony is people have been asking the question, “What is a photo?” for at least 160 years, if not longer. The reason this conundrum is so difficult to answer is that it’s entirely subjective: The photographer may consider their photograph to be one thing and their audience another—and neither can be proved definitively right because the photographic medium is not a monolith. It never has been.

As early as 1860, Oscar Gustav Rejlander was experimenting with multiple exposures to create composite images to describe a narrative. In the 1920s, artists in the burgeoning Dada movement embraced similar photographic montage techniques to create a variety of different work. For example, El Lissitzky (Lazar Markovich), created graphic self-portraits and portraits of other artists; László Moholy-Nagy made “photograms” from various everyday objects.

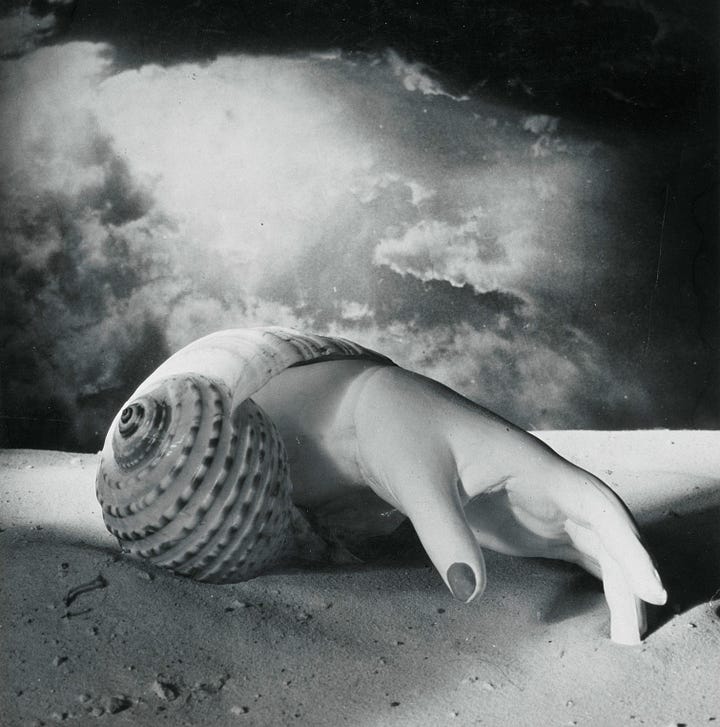

But perhaps the most famous surrealist photographer of all was Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitzky). After moving to Paris in the early 1920s he began experimenting with cameraless photographic techniques, branding them as “rayographs,” montages of people and objects and even a gun and letters of the alphabet. As an artist, Man Ray would draw and paint with graphic blocks of color. But he felt liberated by this new medium of photography exclaiming, “I have finally freed myself from the sticky medium of paint, and am working directly with light itself.”

A decade later, in the 1930s, photographer Dora Maar (who was also a long-term partner and muse for Picasso) used similar techniques to Man Ray, creating bizarre (in a good way) photographic montages, some of which were akin to the GenAI of the day.

It may be hard to argue that the work of Man Ray and the other Dadaists in the 1920s and 1930s are the first to come to mind as examples to answer the question, “What is a photo?” They are, by very definition, surreal and hardly typical—even by the standards of their time. But, they are perfect examples of just how broad the definition of what a photograph can be.

Today, in this era of “Fake News” supercharged by AI manipulation (and sometimes false accusations of AI manipulation), a core element of the current discussion over what constitutes a photo is once again becoming focused on what is real, especially as this new AI-powered composite photography is inherently deceptive and potentially dangerous: If people can easily add themselves or others into photos, or “magically” remove unwanted people or elements in the background, thereby creating moments in time that didn’t technically exist, audiences could easily fall for the fake imagery believing it real, or conversely, won’t believe that anything is real because of how easy it is to fake.

While either outcome is technically possible, I would argue that none of these AI tools are more threatening or deceptive than Adobe’s Photoshop or other “traditional” photo editing tools. The idea that the camera never lies has been proven false almost from day one. Photographs have been manipulated for a variety of creative reasons as well as storytelling ones since the beginning—some of them nefarious.

What we’re really discussing is not whether this new technology is problematic in and of itself—creating images that look real but aren't is literally nothing new—but instead the potential dangers of making such powerful tools available to billions of people. And that, I agree, is a genuine concern.

As AI becomes more prevalent it stands to reason that it becomes increasingly more important to disclose exactly when an image has been manipulated; it’s a safety issue.

Conversely, disclosing that AI has been used shouldn’t mean a photograph is necessarily judged as being less of a photo from a creative or artistic point of view. Reportage photographs that adhere to a certain code of ethics are no more an accurate definition of “What is a photo?” than one created by Man Ray—in the same way classical or jazz genres don’t define music any more than a pop song by Taylor Swift.

With the advent of the smartphone, the gap between capture and process closed to the point as to be almost instantaneous and indistinguishable.

We arguably see more photographs today than at any time since the Daguerreotype. We are drowning in imagery, and much of that imagery is manipulated in some form or another, whether retouched or edited for creative reasons or composed or styled for editorial ones—in the case of fashion and entertainment images, probably both.

Back in 2013, I wrote that the advent of the iPhone was the tipping point between when the majority of photographs we saw on a day-to-day basis were taken by professional photographers to seeing more and more photos taken by people we knew, or at least we followed. The launching of the app store a year later accelerated this trend by making the process of taking a picture and posting it online even easier.

For years, I thought of capture and processing as being the two sides of the coin that defined photography. Ansel Adams famously wrote entire books on each step of the entire photographic process: The Camera, (which I classify as capture), The Negative, and the Print (both of which I considered to make up the processing bit). And like a coin, neither side was more important than the other; the value is created equally by both.

But with the advent of the internet and digital photography, then smartphones and apps, the gap between capture and process closed to the point as to be almost instantaneous and indistinguishable. Now, with the addition of computational photography and GenAI that line has become so blurred that differentiating between the two is meaningless.

In an interview with Julian Chokkattu at WIRED, Isaac Reynolds, the group product manager for the Pixel Camera at Google, outlined a concept more akin to art than the traditional interpretation of what is a photo:

“When you define a memory as that there is a fallibility to it: You could have a true and perfect representation of a moment that felt completely fake and completely wrong. What some of these edits do is help you create the moment that is the way you remember it, that's authentic to your memory and to the greater context, but maybe isn't authentic to a particular millisecond.”

The Dadaists would have loved this. The Cubists, too. We have, in effect, come full circle to the point where photography can once again be representative of a scene, not just a record of it. We no longer need photographic film, a darkroom, an enlarger, developer, or fixer to create our images, and now we don’t even need reality. Add Me, Pixel Studio, and AI-powered computational photography, in general, empowers us to take and create images in milliseconds; we can shoot almost anything we want, and we can engineer it to more closely align with our own phantasmagorical point of view—just like the artists in the early 20th century.

So, what is a photo? It’s anything you want it to be. Always has been.

UPDATE: Shortly after we published this essay, The Verge posted its review of Google’s new lineup of Pixel 9 phones. The Verge's Chris Welch also posted an incredible set of pictures on Threads he created using Google's "reimagine" feature (a tool within the Magic Editor), and... well, the photos speak for themselves.

Welch managed to add car wrecks, a helicopter crash, drug paraphernalia around a photo of a friend, bombs in subway stations, and even corpses covered in a bloody sheet in a crash scene to his photos within a matter of seconds just by typing a prompt.

As I wrote in my essay, all of these creative photo editing techniques have been available to photographers for decades. However, up to now, this level of retouching was time-consuming, difficult, and required powerful and expensive computers.

Google's new AI-powered editing tools Add Me and Magic Editor, especially the "reimagine" feature, empower anyone to apply complex and very realistic retouching and compositing techniques—seemingly without any guardrails or restrictions—to any photo they want within seconds and using only their phone! It's not so much what "reimagine" can do but the speed and ease with which it can do it.

But what I find genuinely alarming about this is that there is nothing to alert the viewer that the photo has been altered using AI (except deep down in the metadata) and that the image, or at least certain elements of it, isn't real. This seems incredibly irresponsible on Google's part, especially less than 73 days away from the US election.

I previously wrote that putting these powerful AI photo editing tools in phones "is a genuine concern."

After seeing the photos in The Verge's review and the photos taken by Chris Welch, I now think that was a monumental understatement on my part. To quote Sarah Jeong from her recent essay on The Verge, “We are fucked.” —

—James