The double-whammy of disruption in a post-AI creative world

What are you willing to pay for 100% free-range organic content?

Since Dall-E, Midjourney, and the other AI image generators first appeared, many creatives voiced their fear, frustration, and anger that these tools were trained on their original work without permission or compensation and that, in turn, these new AI tools threatened their future livelihoods.

Dave McKean, the notable British artist behind Arkham Asylum and projects with Neil Gaiman—The Folio Society, amongst others—was one of the first artists I knew to speak out about the perceived existential threat posed by AI to the creative industry. Which came as no surprise to me as I have heard AI art referred to repeatedly as "shitty Dave McKean knockoffs." McKean went on to self-publish "Prompt," a book of his experiments with AI to familiarize himself with its capabilities during the pandemic, saying, "I was going to either retire or respond."

In the years since the pandemic, the collective trauma of which I think added to the apocalyptic sense of foreboding associated with the arrival of AI (which certainly seems to be the case with McKean), I've actually become less convinced about the specific threat of AI to the future wellbeing of the creative industry, or at least, it’s not entirely to blame. I see the adoption of AI by corporations as more of a symptom of advertising-funded media desperately trying to find ways to save money and address the declining revenues lost to Google and Facebook.

What has become clear to me as a creative is that we're now well past the simple wonder of typing a prompt into an AI image generator and seeing low-res images miraculously appear seconds later. I now see AI as more of a helpful tool than a source of finished work, less magic, more machine. And I also see AI as less the sin and more the symptom of massive systemic change to the entire creative business: the art and the commerce. But which of these concerns came first—the chicken or the egg?

I’ve recently noticed a number of photographers and illustrators whose work I know well and whom I really admire experimenting with using AI for images and video. What has struck me about the results is that regardless of how different their styles are from each other, the work they’ve created using AI all looks remarkably similar: Their individual creative style has been subsumed by that of the AI; it’s been assimilated. Resistance really is futile.

There are, of course, notable exceptions. But what seems to be the common denominator between the creatives who have become fluent with AI is their incredibly strong art direction skills and their ability to deliver work with remarkable consistency and clarity. The work reminds me of the musicians who became early adopters of synthesizers like Moogs and Mellotrons in the late 60s and 70s and created entirely new genres of music.

Those early synthesizers were first seen by some musicians as a potential threat to their livelihoods. In 1965, the Mellotron was introduced in the UK as a way to bring the real sounds of a “live” orchestra into your living room; two years later, The Beatles got hold of one and used it to play the opening notes of Strawberry Fields. Bands like Genesis, Yes, Led Zeppelin, and even Radiohead went on to use the Mellotron in ways I doubt that its original inventor, Harry Chamberlin ever imagined.

The Mellotron was specifically designed so that anyone, even with no musical training or ability, could play the real sounds of instruments. Pressing a key triggers the tape loop to play the recording of an instrument or accompaniment; three different tape loops can be chosen for each key. It’s a mind-boggling, complicated piece of engineering for its time. It is also the perfect analogy for AI in that it contains multiple tape loops or recorded sounds of real orchestras and real instruments played by real musicians. Yes, the big band orchestras that the Mellotron was designed to replace did, in fact, disappear, but that was a result of changing musical tastes, not the technology itself. Audiences were listening to a new generation of talented musicians using the Mellotron to make some of the most famous music ever recorded.

Today’s creatives are dealing with a double whammy: a new technology that is simultaneously changing the artistic tools and the business of the creative industry. AI is like Moog and Napster had a baby: the disruption is to both art and commerce.

Many of those same musicians became rich beyond their wildest dreams, making millions, buying mansions in the countryside, and driving Rollers into swimming pools on coke-fueled binges. Whether they recorded their albums playing a saxophone or synthesizer, a guitar or a glockenspiel, the music business didn't care; if you sold an album, you got paid. Synthesizers may have changed the sounds of music, but the technology didn’t fundamentally change the business model; Napster and iTunes would do that 30 years later. As a result, the value of a hit song today is a fraction of what it was decades ago.

Today’s creatives are dealing with a double whammy: a new technology that is simultaneously changing the artistic tools and the business of the creative industry. AI is like Moog and Napster had a baby: the disruption is to both art and commerce.

Like the Mellotron needed The Beatles, AI image and video generators need a creative human touch to be good. But good is not good enough; because of the other externalities affecting the industry, creatives also need to find new ways to be paid for our input.

Even if we agree that AI is a genuinely useful creative tool, many people are still vehemently opposed to using it, and I don’t blame them. AI may be a symptom rather than a direct cause of the challenges to earning a living wage in the creative industry in 2024, and I can't deny that AI is a powerful symbol of those challenges. As Apple recently learned their cost, even though they went to great lengths to destroy real things in a giant hydraulic press to make an ad about an iPad without using AI, it still made everyone rage about the threat of AI. The threat of AI to creativity and livelihood may have become conflated, but that doesn’t make it less real in people’s minds. We need to find a way to address the two issues separately.

Many of the discussions and arguments around the use of generative AI versus other non-AI tools (from paint and pencils to computers, Photoshop, After Effects, and Figma) tend to focus on which is better in an artistic sense.

Yet artistic value is entirely subjective. I think there are plenty of examples of creative people using AI to create imagery that is objectively better than some imagery created by more traditional, non-AI means. But just because I think that’s the case doesn’t mean you should. However, where the argument becomes more nuanced is when it better relates not to artistic quality but to artistic values, not what is, but what it represents.

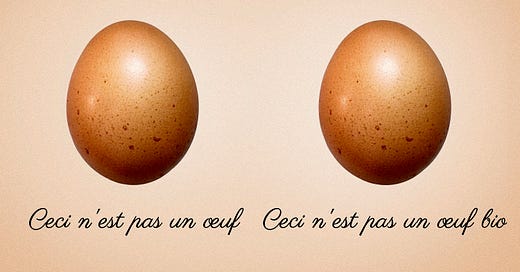

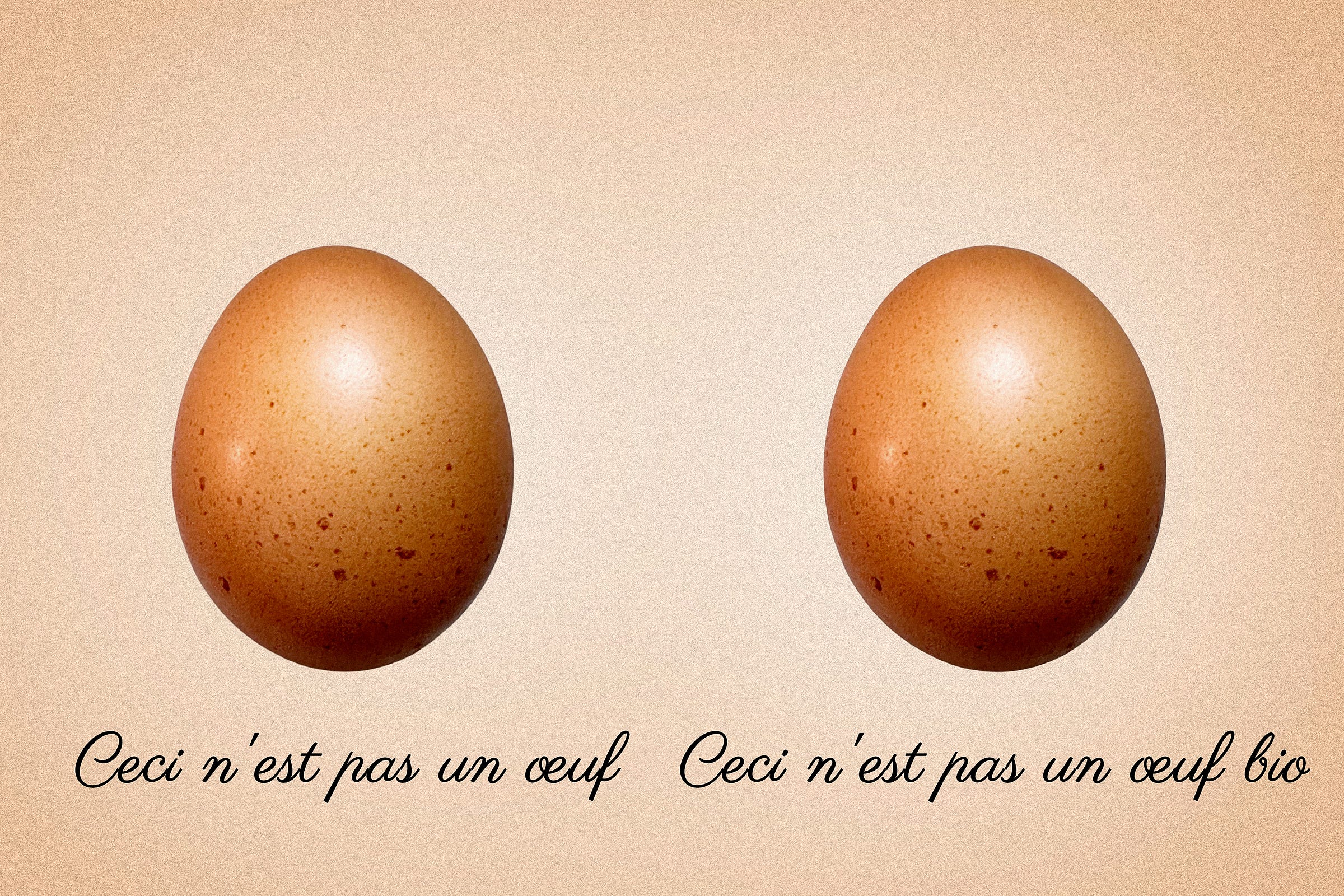

Take organic food as an example. For all intents and purposes, a free-range organic egg is identical to a factory farm egg. An egg is an egg.

Putting aside the fact that the organic egg may or may not taste better (many argue that they do), an organic egg feels better to someone like me because I am a vegetarian and passionate about animal welfare. I am happy to pay a premium for an organic egg because the chickens are cage-free, have room to range outside, and are treated humanely. In short, they have a better life, and that matters to me, so I am happy to pay for it.

Organic food has other values outside of animal welfare: It is grown using fewer pesticides, it’s often produced locally grown or ethically sourced; different factors that may be more important to some people than animal welfare. The benefit depends not on which one is better; it’s what is more important to you.

Exactly the same could be said of creative work. The argument of whether an AI image is or is not better than an image created by a human is not a simple right or wrong answer. But if it is important to you that a human was involved in the creation of an image or a video, that is a real, measurable objective value.

By judging creative work on an objective values-based system as opposed to an artistic merit system, we move beyond semantics and avoid tying ourselves in knots arguing over whether AI is or isn’t bad and instead becomes a simple choice of what you are prepared to pay for: How much extra would you pay to know the art you’re looking at was made by a human? Would you pay a subscription to a publication where all the creative content was created by AI, or would you need to know that humans were involved before you’d spend your money? It’s capitalism, baby.

We have plenty of models for paying for creatives we want to support, from gamers streaming on Twitch to video creators on YouTube. The times have changed. Unlike my Boomer/Gen X generation, who thought that taking money from the public was somehow selling out, the Gen Z generation has embraced micropayments to the creators they want to support, and I think the creative industry is much better off for it. It’s liberating that power has been taken away from the traditional gatekeepers who controlled who did and who didn’t work.

I personally see AI as a powerful creative tool, and I hope to continue using it that way. But I value human input, the human intent. I think it is better that a human made a thing for another human rather than just typing a prompt into AI and accepting whatever it comes up with. This is literally why MBH4H exists: I want to find innovative ways to pay humans for the creative work they make.

In the meantime, I’m going to look for a turntable to buy so I can start collecting vinyl records again. Not because they sound better but because they’ll make me feel better about what I’m listening to.

Audiophiles, please don't @ me.