After the recent reveal of Google’s bonkers AI-powered “reimagine” and “add me” features threatened to upend the very concept of what is real in a photograph, I’ve spent some time shooting black & white photos using my Leica M6, partly as a respite from all of this AI nonsense but mainly just because it’s nice to be taking photos again on film. Of course, I haven’t seen any of those photos yet because I have yet to process the film; I am once again fully embracing the power of the latent image to make me wait.

As people began using the AI photo editing features on the Pixel 9, what struck me most about the photos (if we’re still calling them that) of dragons on rooftops and bears in the street I saw posted across social media was the immediacy of the medium: Shoot the picture, type a prompt using “reimagine” and presto, anything you can think of is instantly made manifestly real, in good ways and very bad. My poor Krell.

No, no dragons or bears (thankfully) for me. I walked in the woods and took photographs of bark and leaves, of clouds and skies, and of rivers and fields. All I’m left with is the memory of what those images looked like through the viewfinder at the time I pressed the shutter button. I won’t see the actual images until I finish shooting the remaining three rolls of Ilford FP4 I have in the fridge and get the negatives and contacts back from the lab. That could be weeks from now.

And so, to pass the time, I also recently began sifting through my archive of negatives, slides, and prints that arrived from the UK earlier this year. I am only now getting around to opening the boxes, in part because I am inspired to look at my old work again after writing so much recently about photography, “what is a photo,” and AI in general, but also because≠ I need to tidy up. I am experiencing a little dose of nostalgia in the process.

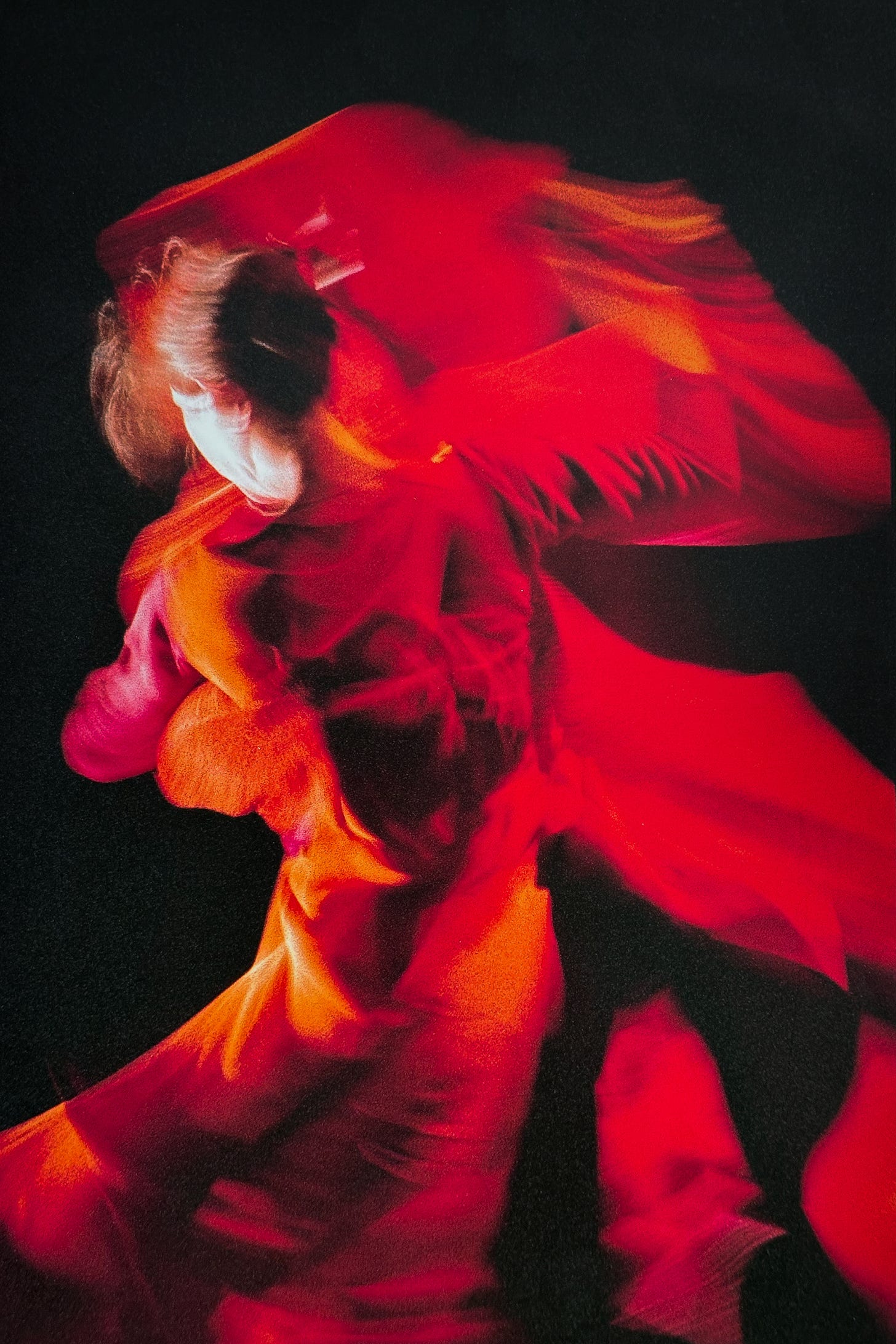

There are a lot of files to go through. Literally thousands of negatives, hundreds of transparencies of all sizes and formats, and boxes of prints. Amongst the portraits of actors, musicians, and F1 drivers, I found a series of abstract, blurry images I haven’t seen for years: photos from my Rambert Dance exhibition, a series of action pics from one of my last shoots of Starlight Express, the Andrew Lloyd Webber show that originally ran in London from 1992-2002 (I was the principle photographer for the last few years of the run); and a couple of images from the late 90s of a young Filthy Dirty, a musician friend of mind wearing a bizarre cardboard mask with a photocopied child’s face while wandering around the London Underground and Piccadilly Circus for no apparent reason I can remember other than we both thought it was funny.

What ties this disparate set of images together is that they’re each a literal moment captured entirely in camera. There is very little post-production—just a small amount of dodging and burning, and in the case of the Rambert image, adjusting the scan of the negative; this image was printed digitally. Most of these photos came as a complete surprise to me when I first saw them in the contact sheets. I had no recollection of taking most of them. They were a shot in the dark (some quite literally), a best guess, a pure experiment.

I have written before about my idea of the vinylfictation of the creative industry: Using analog tools that require more deliberate intent, techniques that aren’t necessarily better but that feel better to the artist and the audience. I have also written in praise of making mistakes, of the importance of not only getting things wrong but also pushing oneself to make those errors in the first place to learn. These images capture all of this and more.

Looking back through these boxes of photographs taken over 20-25 years ago, I remembered an adage I used to constantly remind myself at the time: To make sure that on every shoot, I got what the client wanted, what I wanted, and something experimental that would either be an unexpected surprise or (mostly likely) end up in the bin (or trash, if I am speaking American).

These eclectic images were taken with the “turn out great or go straight in the bin” idea in mind. If I’m honest, none of these photos deserve to be labeled “great,” yet conversely, I don’t think they deserve to be thrown in the trash. Regardless, I am still so glad that I took them. I had no expectation that they would work at all. They were just random experiments.

On every shoot, I got what the client wanted, what I wanted, and something experimental that would either be an unexpected surprise or (mostly likely) end up in the bin.

Shooting on a digital camera or a smartphone makes this virtually impossible. With digital, you can instantly review the image the moment after you take it. The shoot-it-and-see-later experience of film is entirely different, both from a creative and a practical point of view. You can’t see the latent image until it has been processed, and by then, it is way too late to change it if it’s not right.

And it was this profound fact that terrified me when I used to shoot film professionally. I remember flying halfway around the world, from New Zealand to London, before seeing a single frame from a week's shoot in Auckland. I also remember once being asked by a nervous client to guarantee that all the images I was about to shoot for his agency would come out. I couldn’t. All I could say were words to the effect of, “I’ll do everything I can, but unfortunately, there are no guarantees.” Fortunately, everything was fine.

And, of course, I have also heard countless stories from other photographers of lost film, darkroom disasters, camera back malfunctions, and all manner of fuckups that have happened on other shoots. But there is one particularly horrific tale that has always stuck with me.

There was once a fashion shoot on a cruise ship where the photo assistant forgot to bring the film. He was so mortified that he said nothing and just pretended he was loading the film backs for the duration of the shoot. The photographer only learned of the subterfuge when he returned to London and received a letter of confession from his assistant the following day. By then, of course, it was too late; the photographer hadn’t taken a single photo on the entire week’s shoot. All he had left were the Polaroids.

So yes, shooting on film when your career depends upon it is always fucking terrifying.

But that was then. Today, I am taking pictures for myself. As a result, I now find shooting film as liberating and inspiring. I am more excited about taking pictures again than I have been in years. And I love that I have to wait weeks to see how the pictures are going to come out. That’s the entire point.

So, what is a photo? It’s still anything you want it to be. But, if nothing else, perhaps it should be a complete surprise.